Introduction to Cheque Dishonour case and Legal Remedies in Bangladesh

This article aims to provide a comprehensive examination of the various aspects pertaining to cheque dishonour or bounce, with a specific focus on the legislation governing the matter, legal remedies available for cheque dishonour, penalties, and the liability of loan guarantors in the event of cheque bounce (often wrongly spelled as check dishonour case).

What is a negotiating instrument?:

Any document that guarantees the payment of money, whether on demand or at a future date, is a negotiable instrument.

Negotiable Instrument Types:

Promissory Note:

A promissory note is a document bearing the maker’s signature that stipulates an unconditional commitment to remit a specified sum of money to the bearer or a designated individual at a predetermined or foreseeable future time, or upon demand. “On demand” refers to a note that is immediately or visibly payable.

The bill of exchange:

A promissory note is a written document that is endorsed by the creator and includes an unqualified directive instructing an individual to transfer funds to the bearer of the note or to a designated individual at a predetermined or foreseeable time, or upon request. The instrument in question must bear a direction or order to either accept or pay. Furthermore, the acceptor must acknowledge the direction or order for the instrument to qualify as a bill of exchange.

Pay by Cheque:

A bill of exchange is issued for immediate payment and is payable only on demand at a designated banker.

Bounce of a Cheque (wrongly spelled as check bounce) or cheque Dishonour

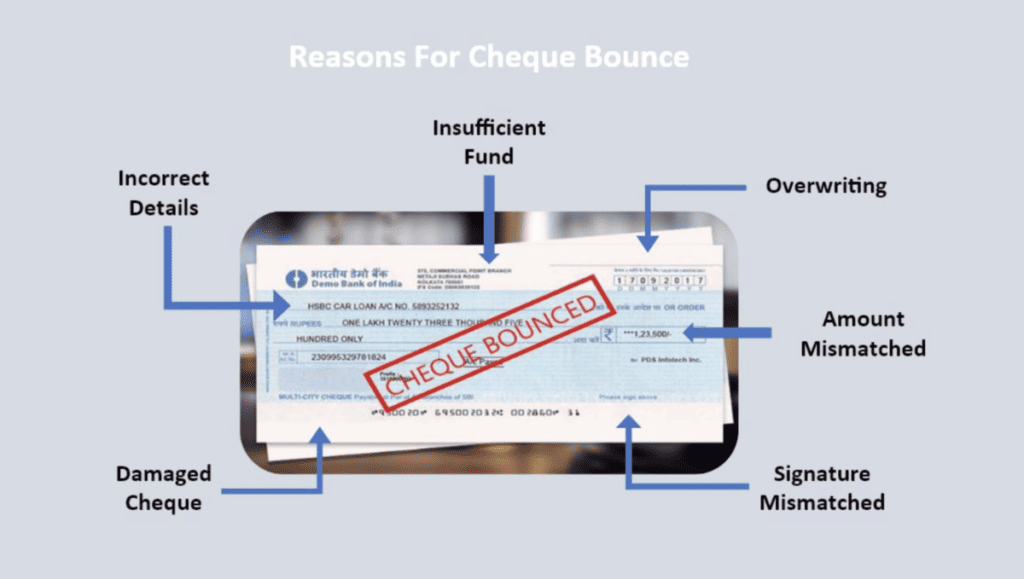

In layman’s terms, a cheque bounce or dishonour of cheque occurs when the bank is unable to honour the cheque on account of insufficient funds. However, from a legal standpoint, it constitutes the dishonour of a cheque, which is an offence, when the bank returns unpaid a cheque drawn by a person on an account it maintains with the banker to be used for paying money to another person from that account. This return may occur due to insufficient funds in the checking account or if the amount drawn exceeds the amount agreed upon for payment from that account in the agreement with the bank.

Additionally, checks may be returned dishonored for a multitude of other reasons, including:

amount discrepancy between the figure and the text,

stale cheque—undated or post-dated—distinct or absent signature of the drawer—payment halted by the drawer—forged endorsement account closure—dormant or blocked cheque—failed to activate the cheque—intimation not received—absence of a forged or unauthorized signature on the corporate stamp

Penalties when a Cheque gets Dishonoured or bounces

The penalties for cheque dishonour and bounce offenses are determined in accordance with the stipulations outlined in The Negotiable Instruments (N.I) Act 1881. This Act is applicable throughout Bangladesh. As the Act is classified as a special law, its provisions shall take precedence over any provisions of common law.

Laws applicable to the dishonour of cheque (check dishonour case):

(i) What are the possible repercussions for cheque dishonour?

In the event that the drawer dishonors the check, the drawee may initiate legal proceedings. As to where to file a lawsuit regarding the dishonored check is up to the plaintiff. It is necessary to file the case in a Cognizance Magistrate Court. In order for the court to have jurisdiction over the disputed cheque, the branch of the bank to which it was presented must be located.

(ii) Procedures for Initiating a Legal Case Pursuant to Section 138 of the NI Act

To file a case for cheque dishonour pursuant to sections 138 and 140 of the N.I. Act, the following conditions must be satisfied:

First, the bank must receive the check within six months of its issuance or during its validity period. Additionally, the payee may present the document to the bank an unlimited number of times, per the drawer’s instructions.

Step two is to demand payment from the cheque’s drawer via written notice delivered within thirty days of the cheque’s return or dishonoured status.

(iii) The drawer shall have thirty days from the notice date to remit payment.

(iv) The drawee is obligated to initiate legal proceedings within 30 days from the date the thirty-day period provided to the drawer for payment expires, should the drawer fail to make payment within the specified timeframe.

Companies Liable for a Claim of Dishonored Cheques:

If a corporate entity commits an offence as defined in section 138, it, along with all individuals who were in charge or responsible for the company at the time of the offence, shall be held liable for the offence under section 140 of the N.I Act.

An individual shall not be held accountable under section 140 if they can provide evidence that they were unaware of the offence being committed or that they made every effort to prevent its commission.

A notice of dishonour served on the firm is adequate to substantiate a claim against a company; notice need not be served on all partners who participated in the commission of the offence.

Prominent principles derived from case law:

According to Shah Alam v State [63 DLR (2011) 137], the drawer of a cheque who intentionally intends to dishonour it is subject to liability under section 138 of the N.I Act.

In FaridulAlam v. State [16 BLT (AD) 2008], it was determined that an individual shall be held liable and prosecuted under section 138 of the N.I Act if he issues a check with knowledge that the account lacks adequate funds. Ahmed Lal Mia v. State [66 DLR (AD) 204] and SM Redwan v. Md. Rezaul Islam [66 DLR (AD) 169] both presented a comparable perspective.

In the case of Khondokar Mahtabuddin Ahmed v State, the Apex Court ruled that a criminal case filed concurrently with a pending civil suit on the same subject cannot be hindered by law. The case Anwarul Karim v Bangladesh, in which it was determined that section 138 of the N.I. Act is not relevant to the recovery of the loan amount, demonstrates this. The criminal case represents the transgression, whereas the civil suit concerns the recovery of monetary damages.

The court ruled in AbulKalam Azad v State (Metro sessions Case no. 152 of 2007) that it is not permissible to issue a single notice for multiple dishonoured cheques; this ruling has since become final.

In disposing of an appeal that was recently filed on 17 February 2020, the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court stipulated that in order to establish liability, a valid reason for the receipt of cheques must be provided. The cheque holder is not entitled to payment from the cheque drawer in the event that the guarantee that was taken into account when the cheque was issued fails to materialise.

The court ruled, “In cases where the amount promised is contingent on additional corroborating evidence or the fulfilment of another commitment, and a cheque is issued in that regard, but that commitment remains unfulfilled, the cheque’s issuer shall not be obligated to honour it, nor shall the holder of the cheque be entitled to assert any claim against the cheque.” The complainant must therefore establish that he provided consideration in order to recover the amount that the drawer guaranteed in the check.

Consequences for Cheque Dishonor

In accordance with the Negotiable Act of 1881, the sanction for the transgression is imprisonment for up to one year, a fine equal to three times the value of the check, or both.

Limitations on the submission of appeals

In order for an order of sentence issued pursuant to subsection (138) to be appealable, the drawer must first deposit at least 50% of the amount that was dishonored prior to submitting the appeal to the court that issued the sentence.

What occurs when the cheque drawer passes away?

The drawer perishes in the N.I. scenario:

Upon the demise of the defendant, the legal proceedings conclude, leaving the complainant with no further recourse but to initiate a civil lawsuit against the defendant’s legal heirs. This is due to the criminal nature of the case as described in section 138 of the N.I. Act, which prohibits the transfer of criminal liability to the accused’s legal heirs.

Drawer passes away in the midst of the appeals process:

In the event that the cheque drawer passes away while the appeal case is pending, the appeal shall be dismissed, with the exception of appeals from fine sentences. The complainant must initiate legal proceedings in the civil court against the legal heirs of the deceased defendant in order to recover monetary damages in the form of a fine.

Available alternatives in the event that the cheque has become obsolete:

A cheque becomes obsolete if it is not presented to the bank and is dishonoured within the time period specified in the act. In the event that a cheque becomes invalid and a lawsuit cannot be filed under the Negotiable Instruments Act of 1881, there are four additional avenues by which one may pursue redress. The holder may, in due course, perform the subsequent actions:

(i) Proceedings under Sections 406 and 420: The holder may file a case for Breach of Trust and Cheating in due course.

(ii) Money Suit: A money suit is subject to a three-year statute of limitations. Therefore, despite the fact that the holder will ultimately be precluded from filing a lawsuit under the NI Act, he will still have the opportunity to pursue the money through a civil suit.

(iii) Summary Suit: Cheques are deemed negotiable instruments in accordance with Order 37 of the Code of Civil Procedure. Consequently, the holder may file a summary suit with the district judge in due course, and the case will be resolved summarily. Likewise, the statute of limitations for the summary suit is three years.

Is it possible for a loan guarantor to incur liability for the dishonored check that the loanee issues?

In addition to the borrower, one or more guarantors are mandatory at the moment the bank grants approval for the loan. It is a well-established legal principle that the guarantor cannot be held liable for the dishonor of a cheque issued by the loanee in accordance with section 138 of the N.I. Act. Nonetheless, he may be held civilly liable for the repayment of the debt he guaranteed (Hardeep Singh Nagra v. State et al.). If the borrower fails to repay the borrowed amount, the loan guarantor will provide payment. If the guarantor issues a cheque to facilitate the payment, he incurs liability under section 138 if the cheque is rejected upon presentation for encashment.

Arbitration and Dishonour of Cheques:

Clauses of arbitration in contracts:

In the event that one party to the arbitration initiates a legal action against the other party regarding a matter stipulated in the agreement, Section 7 of the Arbitration Act 2001 states that any prevailing legislation will be regarded as a non-obstante clause, and the court shall lack jurisdiction to hear legal proceedings unrelated to those outlined in the Arbitration Act 2001.

Ancillary Act of 1881 and Arbitration Act of 2001:

The 2001 Arbitration Act and the N.I. Act are both special laws. The N.I. The act encompasses provisions pertaining to the filing of criminal cases for offenses that are within its scope. Conversely, arbitration proceedings are classified as civil in nature. Furthermore, in the event of a conflict between ordinary law and special law, customary law dictates that the latter shall always take precedence, unless otherwise specified; see Hashmat Ullah v Azmir Bibi and others (44 DLR 332, 337) and Managing Director, Rupali Bank and others v Tofazzal Hossain and others [44 DLR (AD) 260, 263].

According to Probir Roy v. State of West Bengal [II (1996) BC 308 (Cal)], “A criminal proceeding is not covered by an arbitration clause.” It is therefore not possible to evade a criminal trial by invoking an arbitration agreement.

Shahnewaz Akhan v The State and another [19 BLT (HCD) (20110 349)] states, “Pending a civil suit over the same subject matter does not constitute a legal bar to filing a criminal case for criminal liability.”Even if the agreement contains an arbitration clause, a victim may still file a criminal complaint. Similar opinions were expressed by the court in Mohd. Majharul Hoque Monsur v. Mir Kashim Chowdhury and another [2016 (2) LNJ 259, 261-262].

The petition for a writ in the presence of an arbitration clause:

Md. Mobarak Hossain v The State and Others [2011 (XIX) BLT (HCD) 54,60] states that if an agreement contains clear guidelines for the resolution of the dispute, a party to the agreement is not permitted to file a writ petition with the High Court Division.

An appeal of a case brought under section 138 of the N.I. Act:

Arbitration is a civil proceeding; therefore, it is improper to quash a prosecution under section 138 of the N.I. Act due to the pendency of an arbitration proceeding; Sri Krishna Agencies v State 2009 Cr LJ 787 (SC)).

When combined with Section 7 of the Arbitration Act 2001, Section 138:

In Mohammad Majharul Hoque Munsur v. Mir Kashim, the High Court Division ruled that section 138 prosecution and arbitration proceedings can proceed concurrently without legal obstruction. The State v. Shahnewaz Akhand, 19 BLT (HCD) 349.

In the case of Khondokar Mahtabuddin Ahmed v State, the Apex Court ruled that a criminal case filed concurrently with a pending civil suit on the same subject cannot be hindered by law. The case of Anwarul Karim v Bangladesh demonstrates that section 138 of the N.I. Act is not applicable to the recovery of the loan amount. The criminal case represents the transgression, whereas the civil suit concerns the recovery of monetary damages.

0 Comments